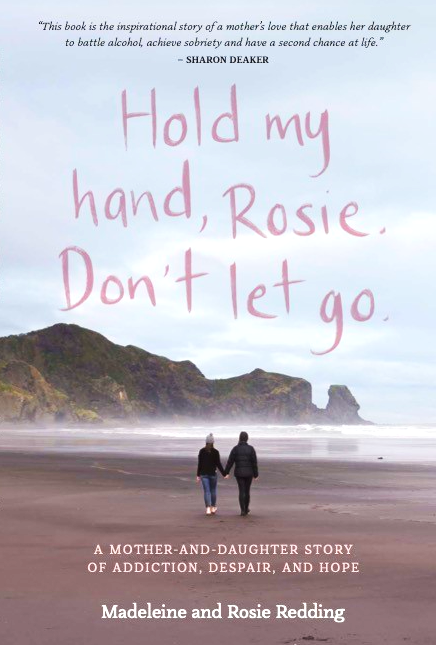

Madeleine Redding completed two writing courses at New Zealand Writers College. Her memoir Hold My Hand, Rosie. Don’t Let Go, co-written with her daughter, is about to launch in Auckland this March. Madeleine shares her writing and publishing process with us.

Can you tell us what motivated you to write this joint memoir about your daughter’s struggle with alcoholism?

Interestingly, I knew I wanted to write, which is why I completed the Creative Writing and Writing a Non-Fiction Book Courses through the New Zealand Writers College.

I was halfway through a novel – in fact, sitting and writing – when I looked at my daughter, who was by then at the end of her first year of recovery. I thought to myself, I would really like to write a story about Rosie’s journey. I asked her, and she was keen on the idea. So I completed the Write a Non-Fiction Book Course, and away I went.

Originally, the idea was that Rosie would just write small snippets, but she wrote so well that her own story grew bigger and bigger alongside mine.

Writing about such a deeply personal and painful experience can be challenging. How did you approach the emotional aspects of telling this story?

I started with the toughest experience first, and yes, it was very emotional. However, with every aspect of the book, there was draft after draft and a requirement to edit and present the best version possible. So the emotions subsided, and the attempt to write well took over.

I do, however, remember ‘finishing’ the book (for the first time), and I was so mentally exhausted that I just went and sat in the garden for an hour.

In what ways do you hope Hold My Hand, Rosie. Don’t Let Go will impact readers, especially those who may be facing similar challenges with loved ones?

This book aims to reach other families going through a similar experience. Rather than trying to present it as a self-help book, which it clearly is not, we hope that some people will read it and realise they are not going through their struggles alone. The book may even strike a chord with those who don’t realise how much their drinking impacts their loved ones.

I don’t believe there is any ‘right’ way to handle a situation such as ours, and I’m sure we got it wrong at times. But being present and continuing to communicate was incredibly important if we were going to have any chance of reaching Rosie.

You started your book while on a writing course. What made you take the course, and how did it help you?

I had retired early from my career as a health professional, which happened to be quite a physical job, and my body was telling me it was time for a change. Writing was unfinished business for me, having always enjoyed it and having turned my grandfather’s memoirs into a book (printed, not published) at my late mother’s request. I really thought I could write!

However, the courses I completed through the Writers College showed me how much I had to learn; I was astonished, in fact, and overjoyed. It’s such a great feeling to get positive feedback on a writing exercise where you really have to think about the construction of a paragraph or short story, to the point that it’s fun to read.

Your memoir likely required revisiting difficult memories and experiences for both you and your daughter. How did you both navigate the balance between honesty and sensitivity in your storytelling?

I was constantly impressed by Rosie’s willingness to be honest with every aspect of her journey, as at each stage we reached, I gave her the choice about whether she wanted to include it. But the worst parts are probably the most important, particularly when she describes the dangers of being a woman under the influence of alcohol.

Could you describe the process of transforming your personal experiences into a cohesive narrative for Hold My Hand, Rosie. Don’t Let Go?

I used what I learned from the Write a Novel Course to make the memoir more readable by recalling conversations and emotions. I wrote in the present tense, while Rosie was a little more detached, describing her experiences in the past tense. I think it works. There was some trial and error, obviously.

You will note that the book is relatively short, with intense moments scattered throughout.

How did you decide on the structure and format of your memoir? Did you experiment with different approaches before settling on the final version?

I researched parent-child memoirs of a similar nature. Honestly, I couldn’t find many. As an aside, Rosie told me there weren’t many out there, which contributed to her determination to be an active part of the narrative.

Of the few that I did find, those written in the present tense resonated with me, as did those that included conversations. However, Rosie wrote her parts in the past tense, and I wondered whether the different tenses would work. I was encouraged, however, by the tutors at the Writers College, where I completed the first half of the book.

Were there any particular authors or books that inspired or influenced your writing style or approach to storytelling?

Double Double: A Dual Memoir of Alcoholism, by Martha Grimes and Ken Grimes.

Beautiful Boy, by David Sheff.

From Binge to Blackout: A Mother and Son Struggle with Teen Drinking, by Chris Volkmann and Toren Volkmann.

Writing about family members, especially when addressing sensitive topics like addiction, can present ethical considerations. How did you navigate these considerations while writing your memoir?

My husband and son have contributed a chapter each, so I guess their consent is implicit here. A significant reason for our pseudonyms and the name changes of all those mentioned in the story is to protect them. Their truths, their journeys and their perception of occurrences may well be different from ours, and we fully respect that.

Also, part of the premise of Alcoholics Anonymous is to be exactly that, anonymous, not because we’re ashamed, but because we don’t want to hurt or trigger anyone. There are plenty of people who know who we are, of course – friends and family. Auckland is a small town. And that’s fine. But all we ask is that if they recommend the book, they use our pseudonyms.

That said, Sharon Deaker and Murray Deaker, ONZM, whose comments are on the front and back covers of the book and who make an appearance in the story, were more than happy to be themselves. Between them, they have decades of sobriety and have mentored and helped scores of alcoholics. Murray has kindly offered to be the MC at the book launch.

Memoirs often blur the line between the author’s personal story and the stories of those around them. How did you handle portraying the experiences of your daughter and other family members in your memoir?

Probably by acknowledging in the book that others’ truths may differ from our own. Those within the immediate family had the opportunity to read extracts as we progressed through the book – admittedly an emotional experience for them at times, as the experience can be a harsh revisiting of moments we are now happy to shelve.

What advice would you give to other writers who are considering tackling similarly challenging and personal subject matter in their own writing?

If you know it’s worth it, whether for your own catharsis or to help others, then persevere. But be sure to take plenty of breaks and have light moments. For me, working backwards from the worst experiences was easiest because I didn’t have them hanging over me. Also, accept that there will be many drafts; you don’t have to get everything right all at once. And use an editor!

Where can readers buy Hold My Hand, Rosie. Don’t Let Go.?

Search BookHub to see who has Hold My Hand, Rosie. Don’t Let Go in stock near you. Any bookstore can also order the book for you.